“Hidden Haven” was the last article I wrote for Bolivian newspaper Los Tiempos when I spent two months as a reporter there in the summer of 2007. Puerto Villarroel is still home to some of my very fondest memories: I can’t wait to get back there.

Hidden Haven: Puerto Villarroel wants to become an eco-tourist haven, but must find a balance between selling out and preserving its jungle paradise

If you stay on the bus linking Cochabamba with Chapare´s most popular tourist destination, Villa Tunari, as far as Ivirgazama – then squeeze into a colectivo, you reach the end of the road, the banks of the river Ichilo, and Puerto Villarroel, a village of 200 people. Puerto has almost no tourist visitors even though its proximity to Villa Tunari makes an easy day trip – and it has none of the facilities Tunari has. But what it lacks in public toilets, hotels, restaurants and internet cafes, it makes up for in stunning tranquility and natural heritage, and it is this that makes it a more appealing place for those who seek an escape from civilisation.

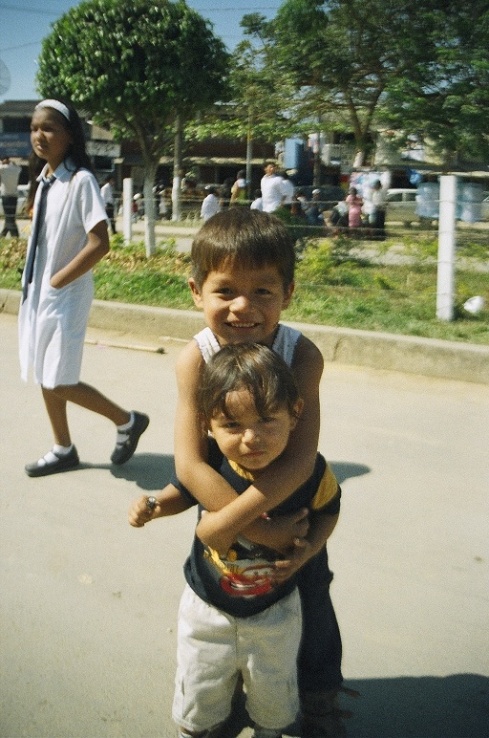

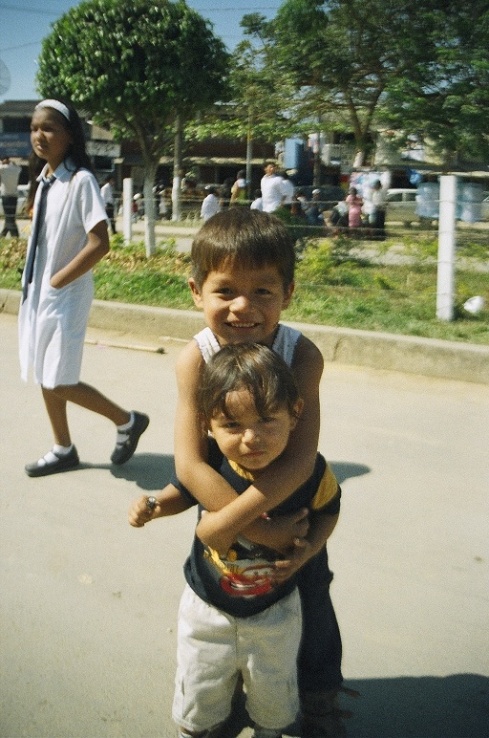

Puerto fits the image one expects of the rainforest. Traditional estiló camba punctuate lush jungle vegetation on the road to the village, and the river. The five-hour bus ride from Cochabamba to Ivirgazama through the Cordillera Tunari, past pine forests and lakes, later ascending into steamy jungle vegetation cradled by clouds, is an incredible introduction to Chaparé; travelling through neighbouring villages gives you a good idea of how different life is there. These villages, like most in Chapare, are financed by the coca trade – but Puerto´s comité civico of five representatives including Jorge Yale, their president, has decided to find an alternative income with the creation of eco-tourism in their little corner of paradise.

Now, there are just two tourists in Puerto, 19 year old Sabrina and her boyfriend Michel from Switzerland, who are here working for free restoring the local Guardería. “I like it here because I all the people know each other, and the climate is beautiful,” Sabrina says. “For me the most important thing about Puerto is the chance that we have to meet local people. It is a special place, especially for Europeans because we do not have the rainforest.”

But for a tourist who has fallen in love with Puerto for these reasons, Jorge´s plan could be a tragedy. The unique selling point that Puerto Villarroel has is this tranquillity. To imagine Puerto full of video camera-carrying tourists is sad. Jorge is aware of this and is keen to avoid over selling.

Puerto could benefit from tourism but, aside from assistance from USAID, the town must do it alone. Abstaining from the coca trade has meant estrangement from other towns, while the alcaldia of Puerto works in Ivirgazama – a designated “red area” for the coca trade, though the number of shiny four-wheel drive cars with 2007 registration plates in Ivirgazama mark out real coca territory – so financial and moral support are not available. Half of the money earmarked for Puerto Villarroel is spent in Ivirgazama, Jorge says, and the other half is not enough to do much with. But Puerto is determined to bring the concept of sustainability, something new in Bolivia, to tourists in Chaparé.

This trade is counter to Puerto´s eco-tourism plan. Cocaleros cut down areas of rainforest to extend coca and marihuana plantations in what is supposedly protected land belonging to indigenous populations like the Yuqui, Yuracaré and Trinitario. “The government does not realize that we can make money without cutting down trees,” says Yale. “Eco-tourism is a good alternative because our main resources here are nature and cultural heritage.” He adds that there are a lot of chemical by-products from cocaine production dumped into the rivers damaging the local eco-system and killing fish stocks.

The comité civico wants to build basic infrastructure, including better streets, gardens, medical services, and better sanitation. There is a plan for families to rent one room from their homes to tourists, for a home-stay experience that will enable sustainable tourism.

“We believe we can be a model for change in Chaparé, an example for indigenous communities here to see how they can survive in a sustainable way. Tourism is part of that.”

Puerto Villarroel: Facts

How to get there: Take a trufi or taxi directly to Ivirgazama, which should cost around 30-40 bolivianos, from the corner of Oquendo and Av. Republicá. They leave regularly throughout the day and take 3-5 hours. From Ivirgazama take a colectivo to Puerto Villarroel, which takes 40 minutes and costs under 5 bolivianos.

Where to stay: There are three hostels -Sucre, Eco Amazonas, and Jasmin. You can walk to them from the main plaza.

What to do: Relax! Have lunch at El Cliper – the tourist information centre that has an airy café attached – to sample the local fried fish. Take a walk on the hidden path along the river to the sandy beach: take a book and soak up the serenity of the jungle. Later, grab a table under the tin roof at La Rocola on the main plaza, order an ice-cold bottle of Taquiña, and listen to the jukebox. Then walk across the street where you can dance with the locals until the sun comes up.

Trips from Puerto Villarroel: Villa Tunari for the national park, treks, and monkey reserve. Occasional cargo boats take passengers to Trinidad, taking five days.

Eco-tourism: If you want to help Puerto develop, inquire in El Cliper about helping to restore the local guardería, or constructing the farm project which is run by Cochabamba-based volunteer organisation, Projects Abroad (www.projects-abroad.co.uk)

Tags: Los Tiempos