My second piece for HR magazine, and one in which I found hardly anyone wanting to go on or off the record. I think I clocked about 15 finance director calls and almost as many HR directors. Goes to show that FDs, who are the top numbers people in their organisations, don’t want to know the return on everything the company does – though it’s interesting to consider whether they should, and how they could do that. I once had a boss who told me that each page in the magazine I edited, if the magazine is working, should have the same and specific cost, vis-a-vis my monthly editorial budget (I forget the number). He was bean-counting it. I thought it was stupid. But then companies need to know what their outlay is to know their profits.

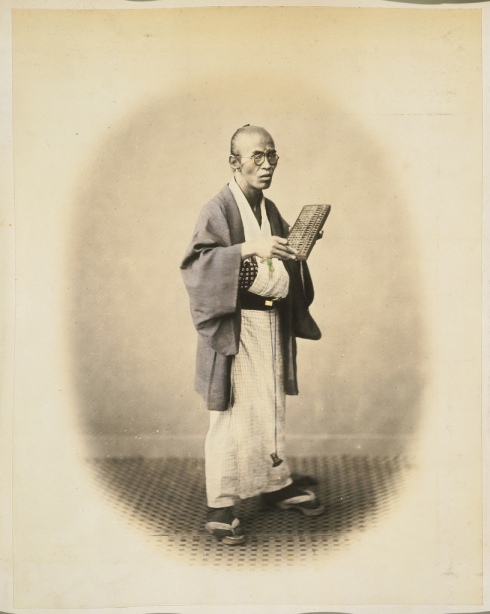

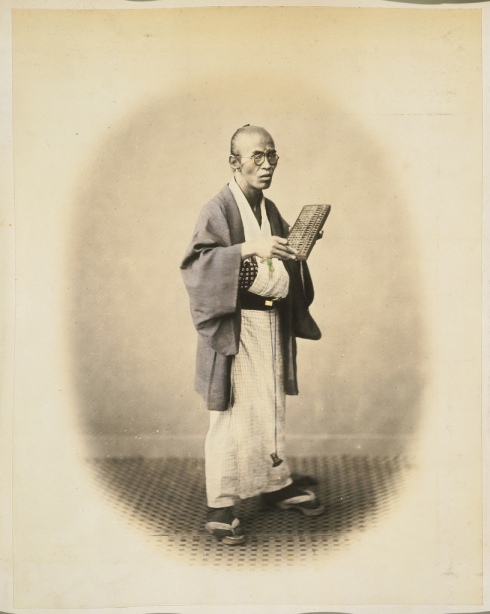

By the way, doesn’t the term ‘human resources’ make your blood run cold? Ah, we are but wooden beads on an abacus: assets to be counted, sweated, used and abused. The word ‘human’ there is not really more than a figleaf – we’re merely ‘droids.

Have a read.

Japanese merchant, identified as “Mr Shojiro”, holding an abacus, taken between 1867 and 1869. Flickr/National Library NZ on the Commons

It is funny how, at the hint of a chance to talk about an HR director’s recent success in launching some shiny, new, bleeding-edge benefits system, a contacts book can fly open – and how it snaps shut when you want to talk about how they measure its return on investment.

Even funnier how the same thing happens when you want to talk to a finance director about those metrics.

Of about 10 finance directors approached for this feature, not one wants to talk about how they measure ROI on HR systems, and of the same number of HRDs approached, just two agree to discuss it on the record.

The HRD at one of the UK’s largest retail gambling outlets, which recently bought and rolled out a platform it hopes will help improve service levels, increase staff productivity and reduce staff costs across 10,000 employees, tells me off the record it initially wanted to roll the system out across the entire business – but decided to only use it in one part, because the trial showed “it didn’t forecast the ROI results we initially thought it may”.

That HRD doesn’t want to go into why.

At the same time, the HRD at a large hotel group implementing a system to automate labour scheduling and improve productivity says it is too early to talk about ROI. “We are in the middle of implementation and nowhere near able to comment on how we measure the ROI,” she tells me.

Another knockback comes from the chief finance officer of one of the UK’s oldest employers, which has just started rolling out a self-service system merging payroll and training on one platform for 16,000 people: “The system is only just about to go live, so I have no idea of its impact on the business – and the bit we are most interested in, which will pay staff, won’t be up and running till the autumn.”

Even these titbits open up a plethora of questions: Didn’t our gambling company HRD need to be confident of the ROI prospects before disrupting the business with a trial? Didn’t the hotelier HRD consider ROI measurement before buying in the system? And is it worrying that an organisation’s chief numbers person has no idea of ROI on his burning platform ahead of launch?

Could it be that neither HRDs nor FDs have a clue how to measure ROI on their reassuringly expensive employee benefits, online training, employee engagement and payroll systems – so simply don’t?

As another finance director – who prefers to remain anonymous – tells me: “It is a pretty cutting-edge area.” Why? “I have never done it.” It seems that’s a common response.

According to talent management technology provider SHL, which surveyed its HRD clients in November 2011, just under half of those clients across the globe collect metrics to demonstrate the value of their HR investments – 6% less than in 2011 – although 70% of its clients admit they feel under pressure to demonstrate ROI on the hire assessment platforms they use.

Interestingly, 42% of SHL’s clients are required by ‘internal stakeholders’ – be they the FD, the CEO or the board – to demonstrate a link between hire assessments (increasingly done through HR platforms) and business outcomes.

SHL’s survey shows that, while more HRDs are being asked to demonstrate the benefit of HR platforms to the company’s bottom line, fewer HRDs are now doing so. And the silence emanating from HRDs and FDs when asked to talk this through is deafening.

The motivation for buying in an HR platform that can automate employee benefits, training and the like often comes from somewhere other than the HRD, says Doone Selbie, an interim HR systems director who works with a range of UK employers on their platform implementations and setting their ROI metrics. With the single metric usually being to save money or reduce headcount, the finance director is frequently the person making that call.

Selbie has often seen HR platforms integrated with those of the finance department. This means HRDs don’t own or have access to the data the platforms produce – so they can’t do any value analysis. “And what they have access to they don’t use, because HRDs, although they are in charge of a lot of processes, aren’t good at process standardisation and ownership,” she says. “Quite often the end-to-end process of an HR platform isn’t within their remit. If HRDs don’t have good processes, it is difficult for them to measure ROI on their systems; if they don’t have good systems, it’s difficult to measure the effectiveness of their processes. Often, they just have a gut feeling that the process needs improving and will buy a new recruitment system for that. They know the system will cut a few days off their hiring process, but they won’t have the time or resources to work out how long that new process is, end to end.”

And the way HR defines a metric is different to how finance does it – another bone of contention. “I don’t think FDs are interested in HR… they report numbers and payroll costs, but the numbers that finance does on HR are to do with cost of employ,” adds Selbie. “And I would say HRDs don’t understand their systems – they don’t see it as their job and they’re not massively systems-literate. They have delegated it somewhere.”

In 2009, mid-sized business publisher Incisive Media built its own employee benefits, training and payroll platform, YouChoose, using its in-house IT team. Some 73% of its UK staff use the platform.

Incisive’s HRD Stuart McLean believes the platform costs nothing, because it was built by existing staff and is run by the existing HR team. It seems more likely the costs are hidden, because no-one wrote any cheques to platform vendors or consultants. Measuring ROI on YouChoose could include the salary costs of staff that were taken off other projects to build the platform and the proportion of time its HR team spends on running it; this data would provide one metric towards the true cost, versus the £100,000 annual saving McLean says the business enjoys from it every year.

“Return on investment is not something we specifically measure. There was no real cost and no budget attached to YouChoose; it doesn’t really cost us anything, because we run it ourselves,” says McLean. “Yes, it does take up staff time, but that is very difficult to measure, because it looks after itself to a large extent.” What about other metrics: does it retain staff? “We would like to think so, but there’s no absolute measure of that,” he says. “What do we get back from it? We believe we are a more attractive employer because we offer benefits, but that is incredibly difficult to measure. Maybe it sounds naïve… but measuring its ROI is just not something we do.”

If HR were a religion, judging the value of a platform by what you like to think it does for staff retention would be adequate. One department that could provide hard-boiled ROI on HR investments is that of the chief technology officer or chief information officer, where they exist. CTOs and CIOs drive efficiency from systems across all parts of a business, and are experts in data collection and analysis to be used in business strategies. In other words, they are the cone-heads who really take an interest in HR ROI.

Information systems (IS) staff, as Selbie terms it, “are the gate-keepers of ROI, rather than the finance people, in my experience. Funnily enough, I see more cases of IS enforcing ROI calculations, justifying the business case for such investments and ensuring a business follows the appropriate project-management steps before investing, than I do from FDs,” she adds.

So many HRDs not only delegate ROI somewhere else, as Selbie says, or don’t see how things such as employee engagement or better employee satisfaction can be measured. Stanley Janas, a former HRD at US performance-management business, Halogen, warns that HRDs can’t hide from the increasing demand for HR ROI for much longer. “One of the things we often hear from customers and prospects is that they struggle to define the ROI of an automated talent-management system in order to justify its purchase,” he writes for Halogen’s blog. “Let’s face it, most of us don’t have deep training in finance, and are sometimes a bit intimidated by the prospect of financial calculations and estimates. But calculating ROI is critical for HR to get support from their business leaders for any investment in talent management.”

Speaking on how finance and HRDs can – or should – work together on ROI, Kathryn Hill, finance director at Crown Paints, dismisses as a mere excuse the notion that HR can’t measure metrics. “A business operates to maximise shareholder value, which is measured through financial results. Human resources has a role in explaining how performance strategies affect this, or how staff engagement impacts on performance,” she says. “It is not about who moves closer to who, but that the two disciplines drive towards the same strategic function.”

Do HRDs and FDs understand why they should know the ROI on these platform investments? They often say they do, but the evidence is stacked against that assertion. Incisive’s McLean says that his CFO is happy with the savings YouChoose has brought the business, but that ROI doesn’t come up in conversation at all. “If the organisation doesn’t force the HRD to measure HR ROI, they won’t do it. And the people to force it are likely to be the IS people more than the finance people,” adds Selbie.

In the future, though, HRDs may be forced by economic imperatives to get familiar with ROI and taking responsibility for process ownership. Jason Averbrook, CEO at HR consultancy, Knowledge Infusion, says the IT organisations he deals with regularly want to support HR, but not by “spending time writing custom reports or designing one-off interfaces between applications”. He believes HRDs need to ask themselves how they move towards a model that removes heavy reliance on IS or IT.

And Selbie adds that HRDs get frustrated with tech people when they can’t grasp how to extract data from their systems.

“They don’t understand all the nuances around the difficulty of extracting information, except that people will tell them it is difficult. They may talk about how long it takes to recruit and how much it costs, but they won’t be asking what their system does to support that and how valuable it is in helping with that – ‘does it give us those calculations?’ They just want to know how to increase the speed of hiring.”

Finance directors, ironically, have a similar mindset.

How do employers measure ROI on their technology systems?

The difficulty in measuring return on investment (ROI) through HR technology is that these tools often give intangible returns that can lead to more effective systems within business, but don’t translate into financial figures.

The Society of Human Resource Management (SHRM) advises ROI of HR technology could be measured as follows:

- Reduced time and resources required to deliver outputs

- Improved data reliability and validity

- Improved maintenance and operational costs

- Contributions to strategic business objectives

- Contributions to strategic talent objectives

- Indirect costs – avoiding unnecessary costs made by incorrect decisions

- Improvements to user satisfaction

- Improved individual and team performance

- Improved attraction and retention of HR staff

With technology, rather than using traditional ROI to measure effectiveness of HR technology, SHRM also suggests employers could consider a cost/benefit analysis. SHRM compares the two methods as follows

ROI

- Appropriate only when both ‘investment cost’ and the ‘return’ come over a short period

- If longer, need to factor in time

- Problem is finding an appropriate investment cost figure

- Sometimes presented as a set of financial metrics, rather than one

Cost/benefit analysis

- No precise definition

- Positive and negative impacts are summarised and weighed against each other

- Include a time dimension

- Attempt to quantify every impact

- Do not exclude an impact if it cannot be quantified

Here are some practical examples of how employers we spoke to measure the value of HR technology:

- Reduction in HR staff time spent carrying out administration processes

- Reduction in staff absence through measurement through online systems

- Reduction in time-to-hire and cost of advertising jobs through use of social media recruitment

- Up-take of employees using e-learning or mobile learning solutions

- Cost savings from avoiding sending staff to training courses or bringing in trainers through e-learning or mobile learning

- Cost savings on purchasing HR software by using cloud technology to store data

- More collaboration between employees and higher staff engagement scores, thanks to more effective internal communications

Tags: Europe, HR magazine